The mother of all Train Operators: BART's Mama Linda on the miles she’s traveled, the meals she’s shared, and the ancestors who shaped her

A recent photo of Linda Yee-Sugaya, a.k.a. Mama Linda, at Daly City Yard.

For 33 years, Train Operator Linda Yee-Sugaya, better known as “Mama Linda,” has said a prayer before stepping onto her train.

“Please let me have a smooth day, a good day,” she whispers before hoisting herself into the cab.

She remembers one of her first rides after receiving her Train Operator certification in 1991. She pulled into Embarcadero Station to find it packed with people on all sides and realized: “When I’m operating a ten-car train, I'm responsible for 2,000 people!” And her job was to keep every single one of them safe.

That early anxiety has long evaporated. But Mama Linda still says a prayer before each ride, just in case.

After so many years in the cab of a train car, the seasoned Train Operator has seen a lot. She’s watched the old trains become the new; stations being built and BART lines lengthen; and thousands upon thousands of faces stream past the windows of her train on their way to parades and protests and celebrations. (Fact: Mama Linda's operated trains during every single Giants Championship Parade this millennium.)

But there is one image, seen through the glare of her cab window many years ago, that she holds most dearly: Her father, Dock Ong Yee, waving at her train on the platform at Glen Park.

“My father thought it was the greatest thing that I worked at BART. He would brag to all his friends, ‘My daughter drives the BART trains!’” she said.

Mama Linda with her father, Dock Ong Yee.

On his way back from Chinatown each day, Dock would take BART from Powell St. and disembark at Glen Park Station, near his house. He’d wait on the platform to see if his daughter’s train went by.

When he didn’t see his daughter pass through the station, Dock would walk up to the cab window and ask the operator: “My daughter, Linda, is an operator. Is her train behind you?”

The trouble was, he always said “Linda,” and without fail, the operator would respond, “Who is that?” Most people at BART knew her then and now strictly as Mama Linda. We’ll get to that story later.

Dock would then go to Mama Linda and say, “How come you’re never on the train? I ask for you, and the operators never say you’re there.”

She’d reply: “Daddy, I am on the train. You have to ask for Mama Linda.”

Only once did their schedules align at Glen Park, he on the platform and she in her cab. Dock got in the first car just behind his daughter’s cab and rode with her to the end of the line. Mama Linda then drove him back home in her car.

Mama Linda grew up in Akron, Ohio. It was the 60s, and the Yees were one of six Asian families in town. Racism and discrimination were routine parts of their life.

Dock immigrated to the U.S. in the early 1940s as a “paper son,” a term referring to people born in China who immigrated to the U.S. and Canada with documentation stating they were related to those who had already received citizenship or residency. On the papers, he was listed as his sister’s son. She lived in Akron, so he did too. A few years after immigrating, Dock joined the U.S. Army and served in China on the “Burma Road.” That’s where he met the mother of his children, Sue Gin Yee, who died in 1957 when the kids were very young.

Dock owned a laundry, and when Akron was undergoing urban renewal in the 60s, the city bought the building. With some moving money in his pocket, Dock packed up the house, and he and his three kids left for San Francisco in pursuit of a better livelihood and more opportunity.

In San Francisco, Mama Linda, 11 at the time, finally began to understand her Asian roots. Back in Akron, she and her family stood out in the crowd, she said. In San Francisco, things were different.

Mama Linda points to a photo of her Train Operator graduating, July 1991, on the massive corkboard at Daly City Yard.

“The first day we were in San Francisco – it was August ‘66 – we walked to Chinatown and saw all these Asian people,” Mama Linda said. “We were amazed. Look at everyone!”

A few weeks later came the first day of school. Mama Linda walked into the classroom and was shocked to find she looked “just like everyone else.” It was a strange feeling, and it took some getting used to.

“I was accustomed to being the center of attention in Akron,” she said. “In San Francisco, I was the same as all the others in my class.”

While growing up, Mama Linda and her younger brother were alone a lot. Their father was working as a custodian at a government building, and her older siblings did their own thing or had moved out. But when the family was home together, the love and joy overflowed.

Dock loved having his kids’ friends over, and he always insisted on feeding them.

“Even my friends called my dad ‘Pops,’” Mama Linda said. “I took after him.”

The “Mama Linda” moniker came into being around 25 years ago, when she was working with a Train Operator in his thirties named Raymond Jew Tsang.

“I’m always telling people what I think they should be doing,” she said. And Raymond was not spared. She always asked him: “Why aren’t you married? Why don’t you settle down?”

“I’d nag him all the time,” she said. “And one day he came over and said, ‘Who are you trying to be? My mama?”

From then on, she couldn’t shake the “Mama” loose from “Linda.”

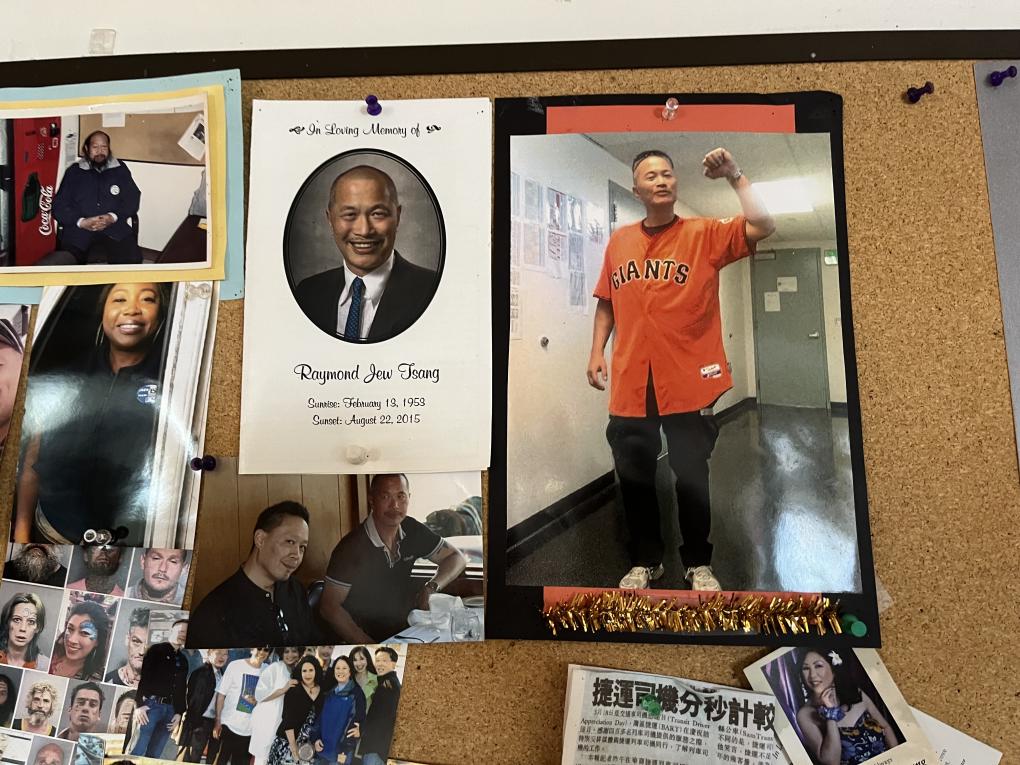

Raymond Jew Tsang is memorialized on the corkboard at Daly City Yard.

Raymond passed away in 2015, and photos of him are still posted to the giant corkboard that’s overtaken a wall in the Daly City Yard breakroom that is so comfy, it feels more like a living room or den. Raymond, Mama Linda said, never did settle down.

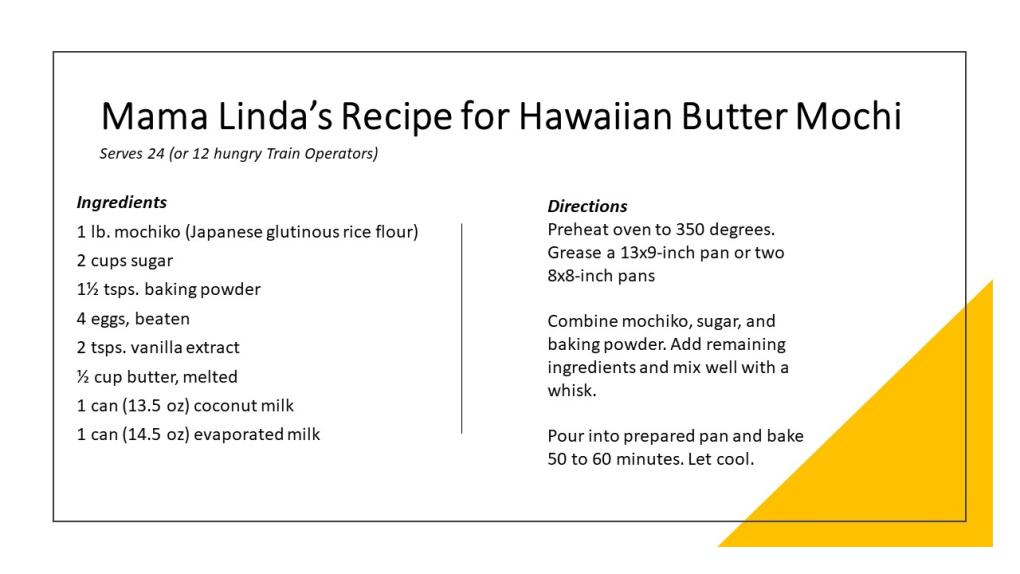

Years after earning her nickname, Mama Linda is still mama-ing. She brings food to the Daly City breakroom – and often entire meals for her colleagues to cook together – pretty much every day. Just like her dad, she wants to make sure her friends are well fed.

“Train Operators are in and out throughout the day, and they don’t always have lunch. This breakroom is our second home, we spend so much time here. So I try to keep stuff on the center island in the kitchen,” she said.

On days when the team cooks together, they gather in the kitchen and get crafty with the hot plate, toaster oven, and Instant Pot (donated by Mama Linda herself). Typical meals include pulled pork, Japanese curry, and “hot dog, hamburger, and root beer float day.” On Cinco de Mayo, the on-duty operators made tacos.

At home, Mama Linda said her husband, Alan, does all the cooking.

Mama Linda plans to retire next year, and as these things usually go, she’s feeling bittersweet about it.

“As my career here concludes, I’m just grateful for the last 33 years,” she said. “It’s been a great experience. I think what I’ve gotten out of it the most is the people I met here. I have lifelong friends thanks to BART.” And lots of treasured recipes shared and tested in the breakroom.

She will certainly not lay idle in retirement, however. She likes to craft, travel, and shop. But she’s most excited to sleep in. Those 3:30am wake up calls get old after 33 years. She’s also thrilled to have time to attend her soul-inspired line dancing class. It’s like line dancing, but to soul music – RnB and Motown and oldies.

“My husband doesn’t like to dance,” said. “In line dancing, you don’t need a partner.”

As Mama Linda winds down the BART chapter of her life, she’s already making arrangements to ensure the culture she's stewarded for so long is thoughtfully maintained.

“I’m leaving all my kitchen stuff here, my Instant Pot and everything,” she said. “And I keep asking, OK, who’s going to do the next party?”

This AAPI Heritage Month, she also plans to participate in the events taking place in Japantown, near where she lives. She likes to stay active in the neighborhood.

“I’m proud of my heritage, to be in this position now, to be living this life, knowing what my ancestors have gone through,” she said.

Mama Linda thanks her stars that her dad moved the family west when he did. She went back to Akron in 2007 for the first time since she’d left as a child. Her mother is buried there, so she and her siblings made a pilgrimage to visit her as well as their living relatives in Cleveland.

“It was a coming home thing, but I was also like, geez, I’m glad I don’t live here,” she said. “I love the diversity in the Bay Area. I couldn’t live anywhere else.”

BART wishes you a wonderful Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Heritage Month. More than 24% of BART employees are members of the AAPI community (as of May 1, 2024), and we want to honor and recognize the ways their heritages and cultures have contributed to BART and our region.

In celebration of the month, BART Communications interviewed Ni Lee, Group Manager and Deputy Project Director for VTA’s BART Silicon Valley Phase II Project. Lee discusses growing up between Taiwan and Southern California, the many lessons she learned working in food service, and shares her favorite recipe for hot pot dipping sauce.

BART celebrates heritage and diversity months throughout the year, and with stories such as Lee’s, we want to recognize some of the exceptional employees in our organization.

Read about two other amazing AAPI BART employees:

- From McDonald’s and Dennys to trains and trackways: How working in food service formed top engineering manager Ni Lee’s work philosophy

- Crisis Intervention Specialist Caryl Blount on BART, family, and food

And check out BARTable’s suggestions for celebrating AAPI Heritage Month near BART stations.