BART helps connect homeless Vietnam veteran to a home of his own

By MELISSA JORDAN

BART Senior Web Producer

If you've walked through Montgomery Station in the past five years, you might have noticed Jack Hanna.

Or not.

The wiry, wary Vietnam veteran may have seemed invisible in the rush of commuters grabbing coffee from the Peet’s stand in the morning, choosing a bouquet from the florist kiosk on their way home.

Hanna had no home.

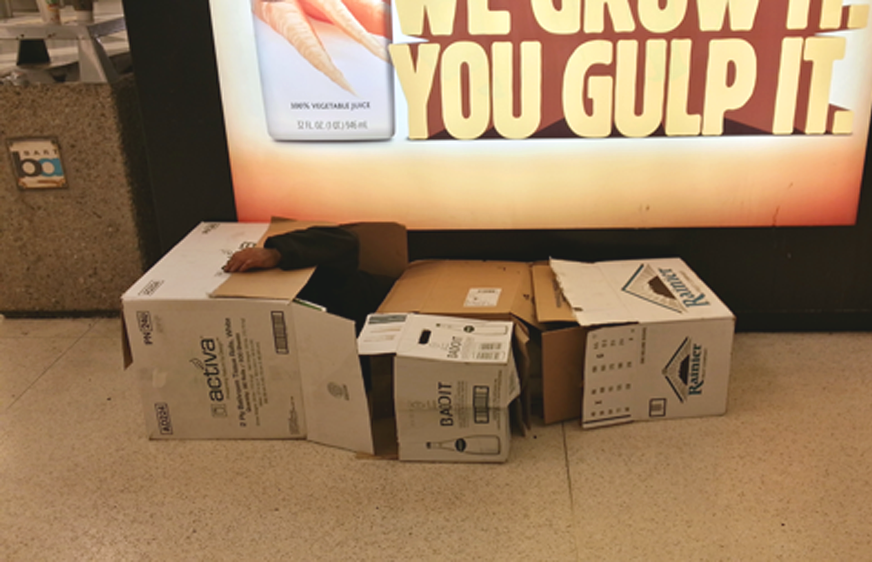

Using some of the survival skills he learned in the military, Hanna lived on the streets and in BART stations, sometimes pushing cardboard boxes together for a shelter.

Hanna "before", when he slept on the floor of a BART station

That changed under BART Police Chief Kenton Rainey, who has strongly advocated a community-oriented policing strategy that helps connect the homeless with services so they do not sleep in stations, which presents a safety hazard to themselves and others if a station were to be quickly evacuated.

SWORDS STEPS IN

Now Hanna has a room in a safe, clean supportive housing building for veterans, run by the Swords to Plowshares organization. With the help of Swords, BART Police, and a host of individuals in the public, private and nonprofit sectors who took the time to care, Hanna finally has a place to call home.

This is his story -- and the story of challenges facing homeless veterans.

BART's homeless outreach coordinator, Armando Sandoval, and officers trained in crisis intervention try to build rapport with the homeless in stations in order to steer them into services that can help. When they meet a veteran, they often turn to Swords.

"I got a call from Armando Sandoval, and Officer Manny Bal, asking if I would go down to Montgomery Street BART and talk to a veteran who was in real bad shape," said Chris Adame, an outreach specialist with Swords at the time. "I sat and talked with him about his military experiences, since I'm a veteran as well, so we could build a foundation to speak on.”

Hanna with Chris Adame of Swords to Plowshares

Sandoval and Officer Bal had made many contacts with Hanna over the years, asking about his health, gently suggesting he talk with the service providers like Swords to find a better living situation.

"We had to get to know him, to gain some kind of comfort level, so he would open up a bit," Bal said. "I think he felt that we were sincere in our efforts to help him, and he actually acknowledged to us that he was appreciative of the steps we were taking, he saw us as beyond police officers."

"This is someone who served the country," Bal said. "Then he is sort of forgotten and kicked to the curb. It shouldn't be that way. Maybe you weren't perfect, but you stepped in to do a duty, and you should be taken care of in some way, shape or form.”

“This is the community policing policy at its best,” Chief Rainey said. “You have to take a step back, find the stakeholders, and work together to begin solving the problem.”

As for taking on such a daunting task, with such complex causes and interests to balance, Chief Rainey is resolute that progress can be made and giving up isn’t an option. “I don’t accept that,” he said. “We can do better as a society.”

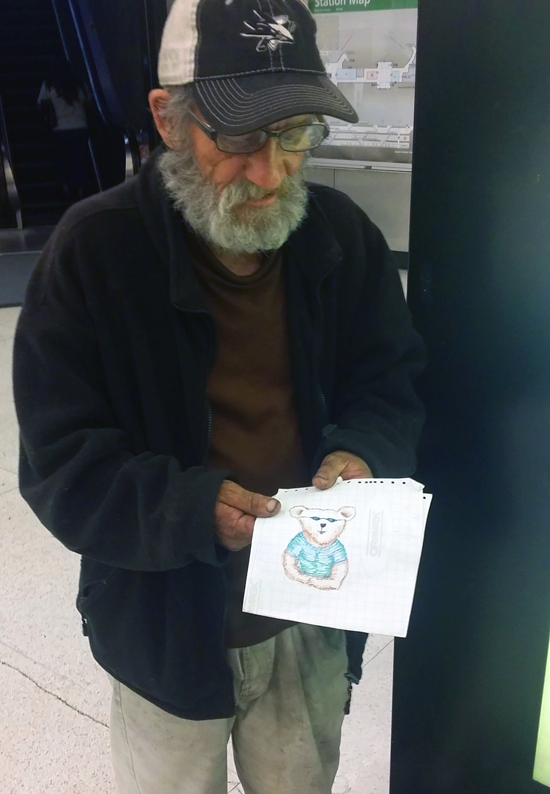

Hanna's hobby in stations was making sketches, like this teddy bear

SHELTER FROM THE STORM

It was mid-December, on the eve of the megastorm that dumped record rain in the Bay Area, with forecasts for chilly temperatures and whipping winds. Sandoval and the Swords workers knew Hanna's health was deteriorating, and that exposure could have devastating consequences. The rush was on to find him a place to stay; a temporary housing facility called Safe Haven in the Tenderloin.

Sandoval, left, Officer Bal, center and Hanna outside Safe Haven in the Tenderloin

"Had it not been for them, I’d probably be dead,” Hanna said.

He recalled the years of contacts with officers, getting shooed out of stations when they closed for the night, coming back to seek shelter, staying awake and sitting, following the rules. The floor was hard, and often dirty. Some people did not treat him well. Why did he go to the BART Station?

“It was warm,” he said, simply. “And it was safer than on the streets.” Initially Hanna lashed out verbally at the police who made him move.

“BART Police would say, “Hey, time to get up, banging on the rails to wake you up,” he recalled. “After I got done cussing at them, they realized I wasn’t such a bad guy, and they were just doing their job of making sure I was OK … I was saying, ‘Why can’t you leave me alone?,’ and they were saying ‘I can’t, that’s my job.’ “

Finally he says, he realized they did care. “I said, ‘If they’re going to help me, I’m going to do my part, too.”

A DAY AT SAFE HAVEN

On a visit to see Hanna at Safe Haven, it seemed very much like the temporary housing it is. Clean, but institutional-feeling, with a locked, grated outside entrance door and a spartan break room where Hanna sat eating his breakfast, a bowl of Froot Loops.

Sandoval and Bal came by to say hello and check on Hanna’s progress.

Hanna with staff at Safe Haven temporary residence for veterans

A gracious host, he offered coffee, and began telling the story of his life. How much has been lost to memory, to the fog of war, is impossible to tell, and some elements could not be verified. But his story was heartfelt, and he came across as an intelligent, contrarian personality who probably landed on the streets through a combination of cruel circumstances and some unfortunate choices.

He remembers a rough home life as he grew up around San Leandro, with alcohol abuse and violence in the family, running with a tough crowd of kids, skipping school. At 17, he volunteered to join the Army, and was sent to Vietnam and trained to be a parachute rigger, the person who prepares parachutes for the soldiers who will jump from helicopters to the ground for combat. Sometimes he also had to jump.

He either doesn't remember, or has blocked out, most memories of exactly what he did there. He remembers using drugs: his unit had the "cloud crowd" that preferred smoking marijuana and the "juicers" who favored alcohol. Such behaviors, veterans' service providers say, were not uncommon for some soldiers coping with stress.

Coming back home to hostility from some of those who opposed the war, Hanna tried to put it behind him and worked a series of jobs, he says, from crane operator to cardboard company handler to unloader of goods for the Salvation Army. That's where he met his now ex-wife. He has a grown child, whom he does not discuss in detail but says was not able to help with his housing situation.

He said he also served prison time for offenses related to his drug addiction, a low point in his life, but that when he got out he was determined to get clean and sober, to turn his life around and never go back.

"You have moments here, looking back on your life, at times when you had some happiness and the times that were not so happy," he recalled. "When I was down and out in the BART station was the first time I ever saw anybody really take an interest and say that they gave a damn. It really made me feel good. All your life, you think good people don't exist, but they do."

LUNCHTIME AT ST. ANTHONY'S

It's time to get lunch, and instead of the hot links boiling on the stove at Safe Haven, Hanna offers to visit St. Anthony's dining hall, another example of the good people he has come to know. They offer free lunch every day at their dining hall in the Tenderloin. Today the entree is pasta puttanesca, with half a baked yam, a tangerine, a piece of bread and a glass of a juice drink. Hanna eats slowly and determinedly; his teeth are mostly gone. With VA benefits now more accessible to him since he has a home, he would be able to apply for dentures.

It seems that all the staff and volunteers know him. "Hello Mr. Hanna, how are you doing?" they ask, as he waves and greets each one. One of Hanna's hobbies is artwork, so he doodles on a napkin. He draws a rose. In the BART stations, he used to sketch happy, comfortable things, like a teddy bear or a tropical sunset.

After lunch it's a quick tour of the neighborhood. "Pill hill," he says of one street, where drugs are openly for sale. He said he does not take even prescription pain medication for his many health issues, because he does not want to relapse into addiction. He points out St. Boniface church, which allows the homeless to sleep on its pews during weekday hours.

It is a rough neighborhood, even if some former dive bars are being turned into suave cocktail lounges and "speakeasies,” at risk of dislocating some of the poor who tend to live there in housing supported by agencies such as Swords.

NAVIGATING THE BUREAUCRACY OF THE VA HOSPITAL

Next up, Hanna has a doctor's appointment at the Veterans Administration Hospital at Fort Miley, on the far edge of the city by the ocean. A VA peer counselor/driver picks up Hanna and another resident of Safe Haven. Hanna explains that he does not like riding in cars, especially in freeway traffic, and he is visibly shaky. He takes a puff from the inhaler he uses for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, one of many medical conditions.

Hanna gets his vital signs taken at the VA Hospital

Inside there are lines, and more lines, paperwork, repeating your info to receptionists again and again. Then the wait. There is time to roam; exploring the glorious views from the hospital cafeteria, overlooking crashing waves set against a robin-egg's-blue sky. When Hanna's name finally is called, he has his vitals taken first – weight in the 130s, he has been losing pounds -- and then goes in for news from the doctor about his liver disease.

He is quiet on the way back. With the late afternoon rush-hour traffic, the driver takes city streets instead of the freeway, and he is calmer. He reflects more on what it is like to have a home, even a temporary one. "It gives you more of a sense of stability," he said. "You have a sense there will be someone there you can call for help."

THE PLIGHT OF HOMELESS VETERANS

It is very common, explains Swords to Plowshares outreach coordinator Randall Flagg, that homeless veterans have trust issues because they have been let down so many times.

"I want to thank the BART Police and their team for the way they treated Jack," Flagg said. "Jack was in the war, and war causes pain and suffering. And a lot of people don't know how to deal with that. Jack didn't know how to deal with that. (The issue of homeless veterans) is not just a BART issue; it's a United States issue. You can sit there and say, 'Why are they homeless?' Well, one reason is they are not getting all of the benefits they deserve."

As an example, without a mailing address, veterans may not be able to get their veterans' financial benefits, or be able to get a job, or access health care to which they are entitled.

"Veterans come in these doors all the time where they have lost their jobs and have become homeless. A lot of them are not even aware of what benefits are available to them. You have to jump through a lot of hoops and it's not an easy process, and it's even harder if you are homeless,” says Flagg, who knows of what he speaks. Twenty years ago he was homeless, and the intervention of a police officer is what he believes saved his own life.

A PERMANENT HOME

Just two weeks after the visit at Safe Haven in the Tenderloin, all Hanna's paperwork was completed to move into a permanent place, a gorgeous renovated building in the Financial District on Kearny Street run by Swords, a mix of that public, private and community support that Rainey talks about – even “sharing economy” home rental startup Airbnb pitched in money and had a volunteer day where employees put furnishings in rooms.

The exterior of Hanna's new home, before remodeling, via Google Street View

Now Hanna has his own room, with private bathroom, and if he can acquire some bubbles he wants to luxuriate in a bubble bath. He has a microwave and refrigerator – even a crisper – “for your fresh vegetables,” he says. “On the streets you couldn’t keep much fresh.” There is gleaming original woodwork, exposed brick walls, common rooms for activities like a recent party where knitting volunteers donated scarves to the residents and a giant sheet cake was decorated with the Stars and Stripes. Hanna chose a soft blue scarf and had a slice of cake and piece of homemade fudge.

Veterans in the new facility celebrate with guests and volunteers

"Look at Jack," Flagg said. "He was written off by everyone. Getting Jack to where he is now was a miracle. It took people believing in Jack more than he believed in himself."

It is a strange and alien world when some chronically homeless veterans finally get a home, Flagg explained. Imagine not having cooked for yourself in a kitchen in years, or decades. Much of what has passed in popular culture, television, the internet, are foreign to you. Hanna hasn’t heard of Facebook, much less Airbnb. He likes being in a safe neighborhood and having a warm bed. Some veterans can’t make the transition to their new homes. Some do.

Local knitters made scarves as gifts for the veterans

There are an estimated more than 700 homeless veterans in San Francisco, according to a recent city count. Nationwide, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development says nearly 50,000 veterans are homeless on any given night.

For now, Jack Hanna is not part of that number.

Jack Hanna, Feb. 14, 2015, right, at a festival in San Francisco. Photo with ink outline filter.

RESOURCES TO HELP

Veterans Administration: Know that one phone call can be the difference in the life of a Veteran who is homeless or at imminent risk of becoming homeless. Make the Call to 877-4AID-VET (424-3838) to be connected 24/7 with VA's services to overcome or prevent homelessness for yourself or a Veteran you know. Read more at: http://www.va.gov/homeless/

Swords to Plowshares: There are many ways to get involved, from volunteering, to tax-deductible financial donations or donations of items in-kind, like business suits for veterans going on job interviews. Read more at: http://www.swords-to-plowshares.org/

BART Police Department: To report a person who may need help to BART Police, you can call 510-464-7020, or use the BART Watch app downloadable from bart.gov/police