BART Train Operator Dewayne Deams on the lessons he learned from his great-grandfather, transit trailblazer Curtis E. Green

Dewayne Deams (left) with his great-grandfather Curtis E. Green at the dedication ceremony for the Curtis E. Green Light Rail Center on May 12, 1987. Photo courtesy of SFMTA Photo | SFMTA.com/Photo

BART Train Operator Dewayne Deams has digital version of an old photo stashed on his phone. The grainy, sepia-toned image shows a boy, smiling and shaking hands with a gentleman in a suit and tie. There's a plaque behind them that reads: “Curtis E. Green Light Rail Center, Dedicated May 12, 1987."

The boy is Deams as a five-year-old. The gentleman is Curtis E. Green, Deams’ great-grandfather and the first Black person to lead a big-city transit agency in the U.S. Green’s impact on public transportation is immeasurable. For Deams, its personal.

“I don’t have a vocabulary big enough to describe how much his legacy means to me,” Deams said of his great-grandfather. “He’s a trailblazer. In my time with him, I never saw him that way. I didn’t realize he's literally in the history books until I was older.”

Deams started asking questions about the man he knew simply as “granddaddy” after his funeral, at which Willie Brown spoke and a letter by Dianne Feinstein was read. Green died in 2002 at 78 after a long illness. Deams, then 21, had seen Brown and Feinstein on tv. He knew they were famous, but why were they speaking at great-grandpa’s memorial service?

Dianne Feinstein, then the Mayor of San Francisco, and Curtis E. Green at the dedication of the Muni Metro Light Rail System on July 11, 1979. Photo courtesy of SFMTA Photo | SFMTA.com/Photo

Deams said his great-grandfather wasn’t the name-dropping type, and he certainly didn’t know him as “the Muni guy.” Rather, he remembers Green as gregarious and easygoing with a hearty laugh. The two talked about football a lot.

After Green died, Deams started researching, and he quickly came to realize his great-granddaddy was a “big deal.” At the African American Museum and Library at Oakland, Deams found a section all about Green and his legacy.

“I had him for a good while,” Deams said. “But when you’re a kid, you don’t always understand the magnitude of things. It’s like, okay, grandpa, whatever you say. I’m grateful I eventually came to learn the importance of what he accomplished.”

Before he fully understood his great-grandfather’s legacy, Deams said he would sometimes brag to friends and classmates when passing the Curtis E. Green Light Rail Center in Balboa Park.

“I’d say, ‘Look at that name! That’s my grandfather,’” Deams remembers. “That was always a claim to fame for me.”

Transit obviously runs in Deams’ blood, and not only on behalf his great-grandfather. Both of Deams' parents drove buses and light rail for Muni. His mother, Denise Green, is now a supervisor at the agency, where she’s worked for more than 30 years. Twice she’s won the distinguished Driver of the Month award, including when she worked in Green’s namesake division. He attended every one of her awards ceremonies.

“The second time she won, while she was working in the Green Division, he came and spoke about how proud he was,” Deams said. “I get choked up thinking about it. That was one of the last times I saw him before he died.”

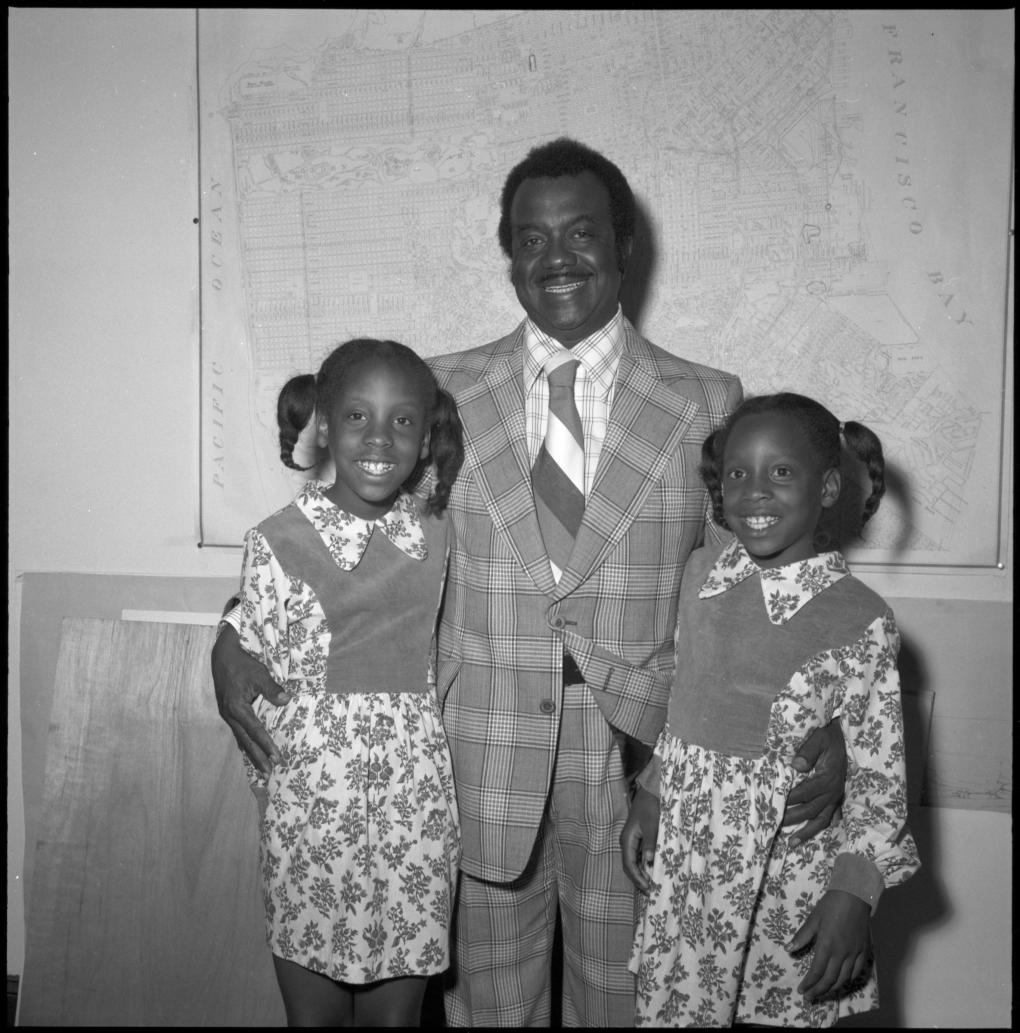

Curtis E. Green pictured with his family on July 23, 1974. Photo courtesy of SFMTA Photo | SFMTA.com/Photo

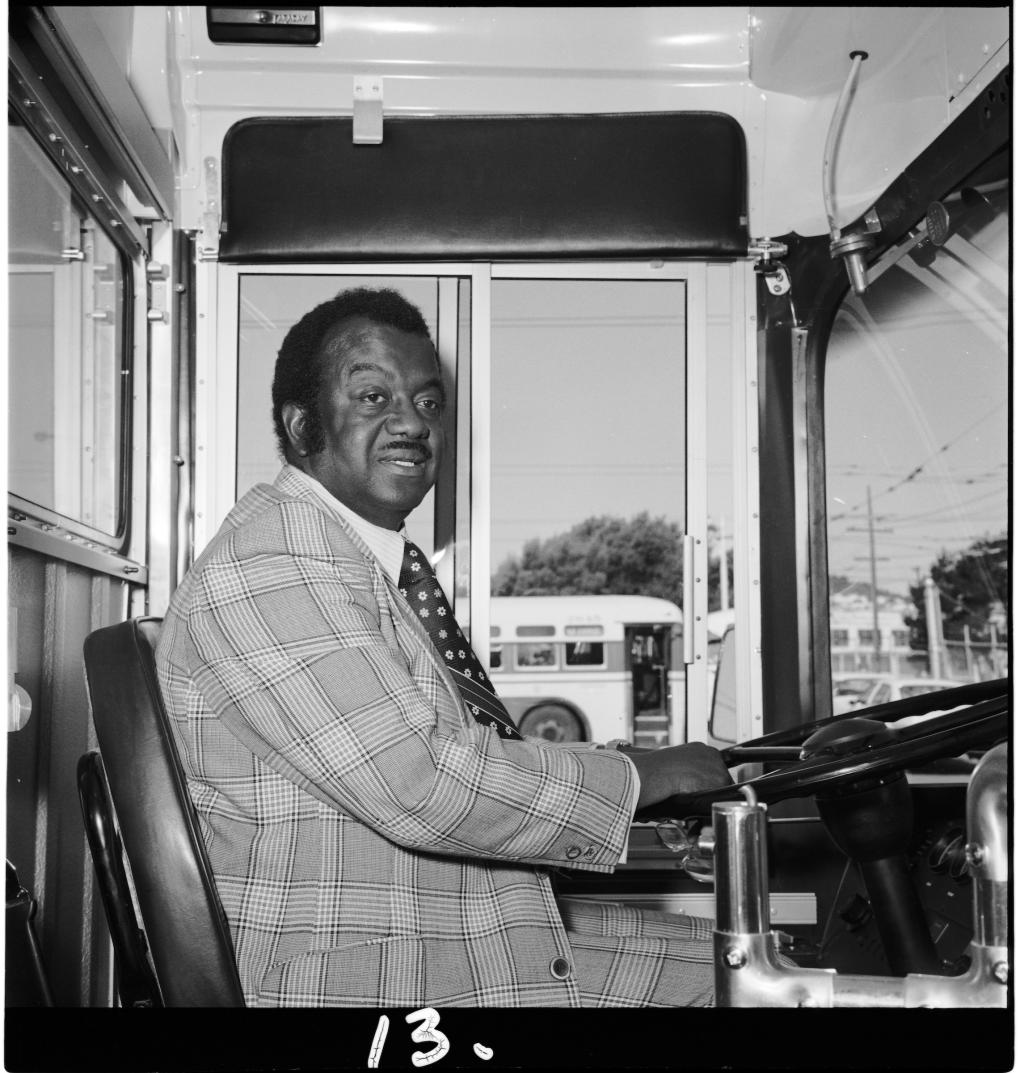

Green settled in San Francisco after serving in the Marines during WWII. Before the war, it could be challenging to find a job if you were Black -- hiring practices were often blatantly discriminatory. The war opened things up a bit, and in 1945, when Green was seeking a job in San Francisco, many employers suddenly had a shortage of workers on their hands. That year, Green was hired as a bus driver, making 90 cents an hour.

Over his 37-year career at Muni, Green slowly rose in the ranks. He knew he wanted to pursue management, and so he did, earning his degree after years of night classes. In 1974, he became deputy general manager of Muni. A year later, he was promoted to the top spot.

Things were not always easy for Green, his great-grandson said. Back in the day, drivers carried change – riders didn’t have to give exact fare – which sometimes made them targets. Green was once robbed and beat up for his change purse.

He faced challenges because of his race, too, especially as he moved up in the ranks. “’You’re affirmative action. You’re only getting this because they needed to hire a Black guy,’” Deams said, parroting colleagues’ racist remarks. Those words stung his great-grandfather, Deams said, but he always rose above it, touting the importance of hard work above all else.

Green loved his job, the city, working with people, Deams said. When he reached the top of Muni's ranks, he treated everyone the same, whether a janitor or mayor of San Francisco.

Deams carries on his great-grandfather’s legacy in his own way, waking up each morning, hopping in his cab, and striving to give BART riders the best service possible. He describes himself as “a major transit nerd” -- one of the lucky few whose passion is also his job.

Deams said his conduct at work is influenced by his great-grandfather and the example he set. Green believed in killing ‘em with kindness and told his great-grandson that there was nothing wrong with being nice. Deams took that to heart, applying it in scenarios as basic as “seeing someone running to the train doors when I’m operating.”

“I could just take off, but I’m a sucker and hold the doors most of the time,” he said. “People appreciate it. You don’t have to be cutthroat. You can be kind and still get the job done.”

A recent photo of Dewayne Deams with his daughter.

One of his favorite parts of the job, like his great-grandfather, is interacting with people. Deams currently works on the Yellow Line, and he loves “walking the platform to my train, answering questions as I go, and seeing people ride from all over the world.” Typical topics of conversation include baseball and how to get to Fisherman’s Wharf. Once, Deams met a woman boarding the train with her father, who had helped build BART back in the 1960s. Deams was honored to take them for a ride.

Having grown up as a “latchkey kid” in the Bayview District of San Francisco, Deams said public transit was a lifeline for him and his little brother. They took it to school, to baseball practice, to appointments. His favorite spot to take the train growing up was Blondie’s Pizza at Powell Street Station. He and his friends would grab a slice and try to scarf it down before the pigeons beat them to it.

As a teenager one evening, while spending the night at his grandmother’s house, Deams remembered convincing her to give him a $20 bill. He grabbed the cash, took the bus to Colma Station, and rode BART to the Coliseum to watch a Warriors game.

“For $20 at the time – it was the 90s – I was able to get there and back, buy a ticket to the game, and get some nachos,” he said. “My mom was pretty furious when I got back though.”

Now, Deams takes his three daughters around the Bay Area on BART, including to sports games. They’re proud of their dad and his career. BART trains aren’t just BART trains to them, Deams said, but Daddy’s BART trains. Just like his great-grandfather did for him so many years before, Deams is now sharing the joys of transit with his children, teaching them how to use it and why it matters.

“They’re in love with trains,” he said. “Especially BART trains.” Nothing could make him prouder.

Curtis E. Green at the wheel of a new AM General diesel coach on May 5, 1975. Photo courtesy of SFMTA Photo | SFMTA.com/Photo