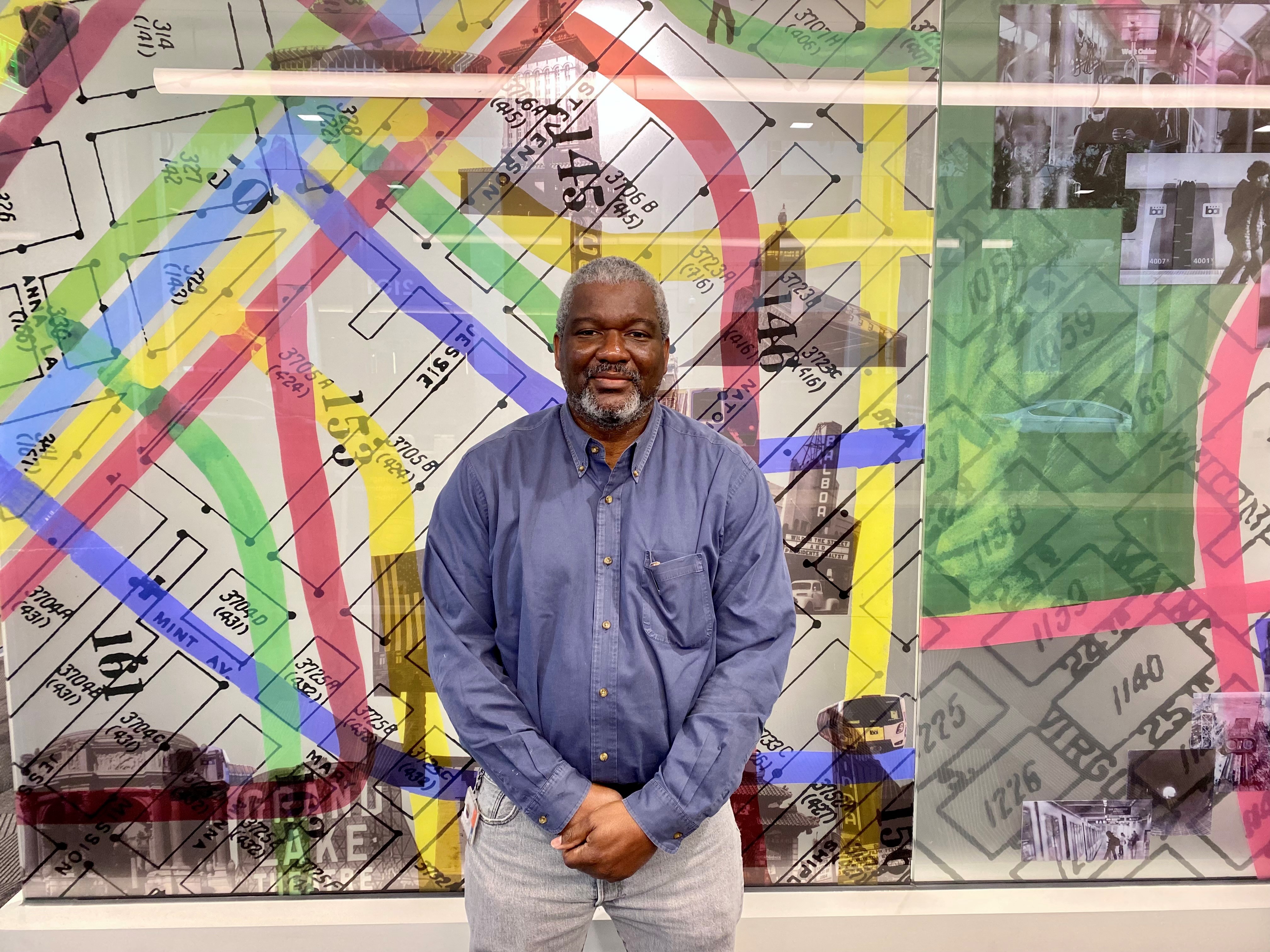

From NYC to OAK, BART Project Manager Bryant Fields, P.E., has seen it all

Bryant Fields, P.E., has never wanted to be anything other than an electrical engineer.

Bryant Fields, P.E., has never wanted to be anything other than an electrical engineer.

When he was around six years old, Fields – now a Project Manager in the Strategic Engineering group at BART – was a huge fan of the “Mission Impossible” television series. One character especially stood out to him: Barney Collier, played by Francis Gregory Alan Morris. Barney was the technical whiz in every episode who devised the spy team’s high-tech gadgets. His fictional resume claimed that he studied electrical engineering at the University of Pennsylvania.

“It was a wow moment; this is what electrical engineers can do!” said Fields when he learned of Barney’s engineering background. The rest, as they say, is history.

Fields had the support at home in pursuing his electrical engineering dreams. His father worked in the construction industry in New York City.

“My father gave me access to his network of associates, and I went to work,” Fields said.

When most kids were shuttling off to camp in the summers, Fields stayed home and worked with his father at various construction sites, including the construction of the Port Authority (1980) as well as the famed rotating restaurant at the Marriott Marquis (1984).

Fields went on to study – you guessed it – electrical engineering in at Newark College of Engineering at New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT). He attended classes full-time at night and worked in construction full-time during the day.

“I’m still recovering from that experience. It was insane, I do not recommend it,” Fields said.

After graduating, Fields had a jumpstart in the construction industry with the perfect combination of credentials and experience. His first post-college job was the hardening of New York’s Hudson River crossings in while working at Lockheed Martin. The Hudson River crossing assets included the George Washington Bridge, as well as the Lincoln and Holland tunnels. Fields said his career has been defined by “big, if not massive, projects.”

A few months after his time with Lockheed ended, Fields got a call from one of the former vice presidents from the company. The VP had a new program for Fields: constructing an airport in Chicago.

The VP told him, “We’re going to demolish the old airport, the Chicago Midway, and build an entirely new Chicago Midway Airport (International) from the ground up.” Fields said the program renderings made him excited.

“I had to be a part of this program,” he said.

Fields agreed to meet the VP and his team in Chicago for an interview. When he got to the greasy spoon where the interview would be conducted on a cold Chicago morning, Fields could feel the skepticism emanating from the other executives, city stakeholders, and airport representatives on the project.

“It was a bunch of construction-hardened white guys with some young black kid sitting at the head of the table wanting to build their airport. They were looking at me with the look: What do you know?” Fields remembered. All it took was the VP giving a nod to signal his trust in Fields. The next question was, “When can you start?”

At the time, Fields was about to turn 30. He was #3 from the top on the organization chart and in charge of the concourse and its 33 gates. He would be managing a team of architects, engineers, schedulers, and construction personnel. Despite his impressive credentials, the executives at the table had another question for him.

“’Chicago is a racist town,’ they said. ‘Can you deal with that?’” Fields remembered. He replied: “My skin is thick, and it can get thicker.”

In the early days of his career, Fields said there was a definitive “look” for project managers and engineers, who were almost always white: pocket protector, buzzed haircut, white shirt, rubber sole shoes.

“That was the picture of an engineer or project manager, whether white or Black,” Fields said. “It was pitiful. When I first went to Lockheed, I had to ask myself, do I want to be one of those cats looking like that for the next 30 years?”

Fields said things changed in the 80s with the advent of personal computers and digital design programs, as well as the development of construction management degrees, which “made the industry more accessible” to a wider variety of people.

“It became more about retooling your brain,” he said of engineering and construction. “The technology, as well as the media, glamorized the profession and made it warmer and more inviting for everybody.”

When Fields was coming up as a young engineer in the 80s, engineering and construction weren’t like that. He said he came in “on the tail end of the old-school regime.”

At BART, on the other hand, Fields noticed “everybody works here, not just that old guard.”

“BART is diverse and has a lot of seasoned professionals who know what they’re doing,” he said. “That’s why I’m still here.”

When the Chicago airport program completed, Fields was on the hunt for his next adventure. He found it in California, at the Oakland International Airport.

On his first day, Fields met his soon-to-be wife. The couple settled in Oakland with their son, where they remain to this day. Fields’ twentieth anniversary of living in California is in June of this year.

After another project, this time at the San Francisco International Airport, Fields decided to set out on his own. He founded a construction and engineering business, which he ran for 13 years.

“You had challenges, but it was more fun than anything else,” he said. The company worked with major players throughout the Bay Area, including BART, Kaiser, Intel, and Cisco just to name a few.

Then, a few years ago, his wife developed early onset Alzheimer’s. Both she and Fields had to shutter their businesses.

“We had to regroup,” he said. “So, we put our planning and project management skills together and said, how are we going to deal with this and work it out?”

Fields’ wife encouraged him to apply at BART, where she’d previously served on the Small Business Advisory Council. It was an adjustment for Fields, but he took it in stride.

Today, Fields has a slew of massive BART capital projects under his belt. Fields started working on track and structures, before transitioning to cable projects. From there, he managed the design and execution of substations in the system. These days, he’s working with the Maintenance department on in-house construction projects.

“I like working for BART because I like working on major projects,” Fields said. “The smallest stuff I work on is maybe a project in my house, and I’m always horrible at it. If it’s not big, I get bored.”

“With technology right now, everything is intertwined,” he continued. “You can’t be confined to your own discipline, and BART is a prime example of intertwined disciplines at work every day.”

After more than three decades as a manager and professional electrical engineer, Fields has endless pearls of wisdom to string. To young and aspiring engineers, he emphasizes the importance of listening, receptivity, reading, and never being afraid to try new things.

“Finding fulfilling work is the key,” he said. “I wake up every morning without any reservations about coming to work. Enjoy the process. Remember that it’s not that stressful and don’t complain.”

Outside of work, Fields enjoy cycling and spending time with his family.