Previously:

The Project Begins

With funds to complete the system assured, construction contracts were returned to their original scope, the work quickly reached peak level in 1969. But three years of financial uncertainty had taken their toll on work schedules. The shortage of funds had also held up ordering the transit cars. When the first 250 cars were finally ordered from low bidder Rohr Industries, of Chula Vista, California, the cost was $80 million ... $l8 million more than the original cost estimate for the entire 450-car fleet. (Subsequently, 200 more transit cars were ordered for another $80 million. Delivery of the total 450-car fleet would be completed by July 30, 1975.)

Meanwhile, federal monies had begun flowing into the project at an increasing rate, making possible a wide range of improvements over the original system plan. BART's widely-known "linear park", for example, was constructed under the aerial right-of-way through Albany and El Cerrito to demonstrate how function could combine with aesthetics to enhance community environments. A $7.5 million program for systemwide landscaping and right-of-way beautification was partly funded by several of the largest federal grants ever made for this purpose. Of the $160 million base cost of BART's 450-car fleet, 64 percent was funded by federal grants.

Included in the construction contract for the lower Market Street subway, awarded in the busy year of 1969, was the basic "box" structure for the Embarcadero Station. Not in the original plans, the system's 34th station was added as a result of increasing development of the lower Market Street area. Station funding was cooperative, with the San Francisco business community raising money for design, and BART spending $25 million on construction. (Of the latter figure, $16 million was raised by curtailing construction of the MUNI subway at the West Portal station instead of St. Francis Circle as originally planned.)

The $315 million, received to date in federal capital grants, was an important factor in upgrading the system from original plans. Nonetheless, this federal aid is only 20 percent of the total $1.6 billion investment in the system. (If BART were being built today, 80 percent of its capital costs could be federally funded under the U.S. Urban Mass Transportation Assistance Act of 1974.)

Thus, changes and improvements increased the valuation of the system considerably from the original estimates...a cost factor that is frequently and incorrectly confused with the true project cost over-runs on specific contracts.

A New Railroad Takes Shape

As the project moved into 1970, the wide range of system construction passed its peak, and contracts were being completed with increasing frequency. An amorphous collection of excavations, stacks of lumber and brick, sections of rail, and giant spools of cabling was taken on the outlines of a finished railroad. Long suffering San Francisco businessmen were even beginning to recapture Market Street from the BART construction forces.

As the system neared completion, the construction engineers so long in charge began making way for a wide range of electronic engineers and technicians, computer experts, and other specialists. Their job was to install and prove out the automatic train control system, plus three maintenance shops and train yards at Hayward, Richmond and Concord, a staggering array of communications and wayside equipment.

The first prototype car was delivered in August, 1970. By early 1971, the ten test prototype transit cars were being operated on the Fremont line in a round-the-clock program to prove out the new design before it went into full-scale production. Meanwhile, at its San Jose plant, IBM was readying the first group of prototype fare collection machines, which it demonstrated to District Directors in October. Since it received an initial $5 million contract in 1968, IBM had been developing a fully automated system to collect fares on a graduated (per mile) basis, as specified by BART, to provide equity between short and long distance riders.

In December, 1971, the District Board adopted the official inter-station fare schedule, ranging from 30 cents minimum to $1.25 maximum fare. Also, approved the following month were 75 percent fare discounts for patrons over 65 or under 13 years of age, with discount tickets to be sold through local bank branches instead of at BART stations.

The 1971-72 period saw the gradual phase-out of major construction work, and the beginning of the transition from a construction-oriented organization to an operating railroad. New areas of emphasis included marketing, personnel training, planning feeder bus service to stations, and across-the-board preparations for revenue service. The District staff, up to 765 by mid-1972, had almost tripled in three years to build up the transportation and maintenance force for revenue service.

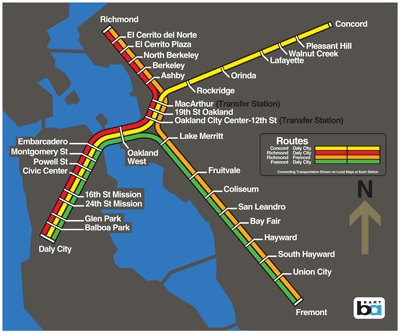

A study of an extension between Daly City Station and the San Francisco International Airport was concluded, and another study of an extension of shuttle access to the Oakland International Airport from the Coliseum Station was continued. Also extension studies for northwest San Francisco, the Pittsburg-Antioch area, and the Livermore-Pleasanton area.

The first segment of the system to open would be 28 miles between Fremont and MacArthur stations. In mid-1972, the District Board set Monday, September 11, as the first day of revenue service.