New life for retired rail cars: Recycled and reused, with some offered to the public

Story by MELISSA JORDAN | Photos by MARIA J. AVILA

BART Communications

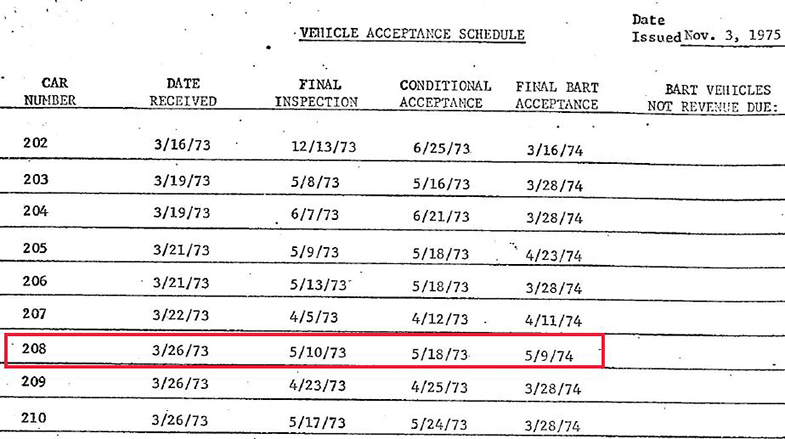

The train car known as BART Car 1208 arrived in Hayward on March 26, 1973, brand-spanking new, just six months after the Bay Area Rapid Transit system opened.

Car 1208 carried millions of riders over the next half-century, until mechanical and structural problems landed it on the list of the first 15 old train cars to be decommissioned. BART is ramping up retirement of old cars as more new Fleet of the Future cars are delivered.

Most of the old cars, including Car 1208, will be scrapped for spare parts and sustainable recycling; a few will be set aside for offer to the public for uses like museums, artwork or training.

The Board of Directors will hear a presentation about the decommissioning process on Thursday ahead of an upcoming contract award for the next batch of recycled cars.

“As we ramp up, at some point, we’ll be recycling one car almost daily,” said Brian Tsukamoto, BART’s Manager of Special Projects-Decommissioning.

REDUCE, REUSE, RECYCLE

The vast majority of BART’s existing fleet of around 650 cars will go through a process just like Car 1208 did.

Train cars with the worst performance are chosen first for recycling, and Car 1208 was showing its age, with train control issues and deteriorating floor panels. “Every automatic train control component on this car was replaced many times over the years,” but it still had problems, said Brian Bentley, Principal Vehicle Systems Engineer. The flooring, which is a huge undertaking to replace when the balsa wood core deteriorates, was the final nail in its coffin.

HOW THE PROCESS WORKS

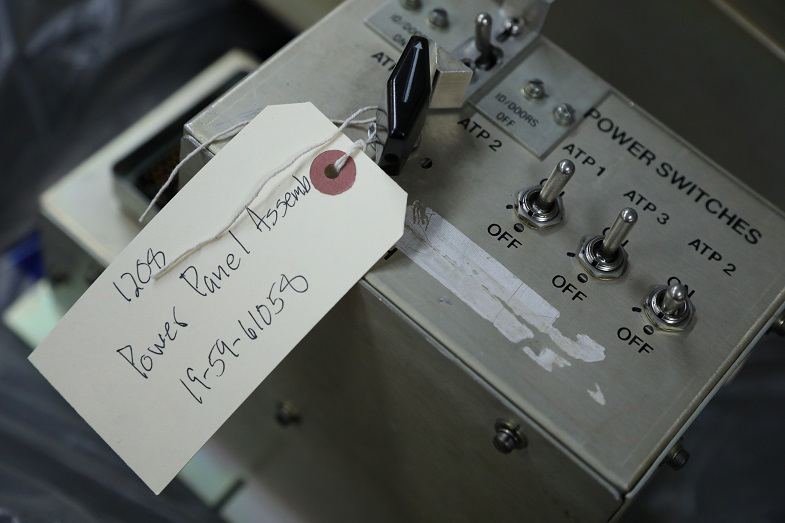

A worker removes components that will be stored as spare parts for other trains

Once a car is selected for decommissioning, crews methodically pull every component that is still in good working order and can be used for spare parts. Workers place a tag on each item to identify and track it for quick and easy retrieval when needed. Blackout tape goes up over the BART logos. The identifying number for each retired car, thus far, has been saved on a kind of memorial wall in the maintenance shop. Hazardous materials are properly disposed of at the BART shop before the train car is sent to the scrap yard.

A power panel assembly is tagged and logged before it goes into spare parts storage

When the car has been completely picked over, typically, giant eye bolts are used to elevate the 60,000-pound car in the shop and carefully guide it onto the back of a low flatbed truck.

In some cases, like Car 1208, a different method is needed. The threaded connections that tie into the car body structure were damaged, precluding use of the eye bolt method. Using a custom-build spreader bar designed to lift all types of BART cars, with two lifting straps in place of the usual lifting lugs, Car 1208 was hoisted onto the flatbed truck. (The contracted driver who hauled the car to the recycling plant in Oakland is known for his ace skills at making tight turns – essential when maneuvering with a 75-foot-long train car on board.)

A worker attaches one of two straps of polyester fibers through each end of the decommissioned train car to hoist it onto a flatbed truck (think dental floss on a massive scale) capable of lifting 84,800 pounds total.

The flatbed pulled into Schnitzer Steel’s facility near the Port of Oakland where Car 1208 was weighed and offloaded. Then a huge machine groaned to life as its operator sunk the jaws into the roof of the train car and tore it into chunks. The metal of the car’s body screeched, windows popped, and at one point, the fragment of a system map fluttered atop a pile of debris.

Car 1208 on flatbed truck arriving at the Schnitzer Steel facility in Oakland

FROM CHUNKS TO SHREDS

Over several days, Schnitzer workers put the big chunks through a series of steps that sort out the different types of metal materials – mostly steel, aluminum and copper – and run them through a mega-shredder that can pulverize them into tinier pieces. It’s a finely tuned process that ends up sending metal materials, on either bulk cargo vessels or container ships, to mills and foundries around the world, to get new life when used in other products that, for example, support critical infrastructure and transportation projects.

Machines at Schnitzer Steel take the large chunks of metal and send them to the shredder

“BART cars are safely cut into manageable pieces before going into our shredder,” said Christian Nordhausen, Schnitzer’s Director of Commercial Operations in Oakland. “It comes out in shreds as small as your fist. The scrap steel from BART cars is sold to mills to create new products like rebar. The aluminum and copper are shipped to smelters and foundries to make new aluminum airplane and car parts, and copper wiring for home appliances and electronics. What we are able to recycle today helps us create a more sustainable tomorrow.”

One train car can yield up to 22 tons of metal – around 15 tons of steel, 6 tons of aluminum and 1 ton of copper. According to the Institute for Scrap Recycling Industries, recycling just 1 ton of steel conserves 2,500 pounds of iron ore, 1,400 pounds of coal and 120 pounds of limestone. And, creating products from recycled steel instead of virgin ore uses 70% less energy and 40% less water and reduces mining wastes by 97%.

Pieces of scrap metal move on a conveyor belt on to a sorting and shredding process

PUBLIC OUTREACH FOR PROPOSALS

BART will be giving the public a chance to have a part of BART history and help in this circle of train car life.

In the coming months, BART’s Government and Community Relations staff will fan out across the region doing outreach to museums, history centers, other agencies that might want retired cars for first responder training, arts organizations and other groups from throughout the community. They’ll be giving a presentation on what's involved to create a successful proposal to retire an old train car.

You can find preliminary guidelines at www.bart.gov/legacycars. Most of the guidance is typical for peer transit agencies who have done similar programs. The proposed use must reflect positively on BART’s brand, for example; it must benefit the community in some way; and the proposer must cover all the expenses to be cost-neutral to BART. That can be more than you think: hiring drivers, obtaining permits, providing required insurance, paying for a crane and other heavy equipment; and covering staff time for preparation of the cars. It’s estimated these costs would be between $8,000 and $10,000 per car (and more if the car will have to be shipped a long distance).

A formal request for proposals will be issued in January; at this time, you may informally express interest by emailing [email protected] with your ideas. Some of the suggestions so far have been to use the cars for public artwork, for tiny homes, for food trucks; or even pop-up retail spaces.

Each proposal must have a concrete and verifiable plan for the eventual permanent disposal of the cars when they are no longer fit for the original usage proposed. As Tsukamoto says, “These are very bulky items. We wouldn’t want someone dumping one on the side of 880 when they’re done with it. You’ll have to follow through on your contract for procuring them.”

Still, preserving a part of the iconic original BART cars has sparked a lot of interest; dozens of inquiries have been made about possibly acquiring one. The queries range from the U.S. Army (national security training purposes) to Burning Man festival-goers (artistic purposes).

Acceptance records show Car 1208 (originally 208, rehabbed to 1208 in 2000) arrived in March 1973

"We're going to work with applicants to make sure they know all the requirements, and we're going to try to set them up for success,” Tsukamoto said. “We'd like to see proposals that make a positive contribution to the community. There are a lot of creative people in the Bay Area, and we're excited to see the ideas for giving these cars a new life."

View and download our brochure about the proposal process, timeline and car measurements.