Podcast: Bond money pays off with improved earthquake safety

Host:

“And welcome to our latest edition of “Hidden Tracks: Stories from BART.” I’m Chris Filippi and this time we’re focusing on a matter very important to BART riders, that of earthquake safety. To learn more about what BART is doing to keep the system safe, I’m joined by Thomas Horton. He’s a manager in the Earthquake Safety program. Tom, thanks so much for your time.”

Horton:

“Yes sir, glad to be here.”

Host:

“I think a lot of folks really are not aware of Measure AA, it goes back a few years. Kind of explain it for us, what is Measure AA and what is it doing for BART?”

Horton:

“Measure AA was a $980 million bond issue, general obligation bond, that was issued for BART to retrofit its existing, original existing system against likely earthquakes in the Bay Area. It was based upon a study that we had done identifying the vulnerabilities in the system and proposing a retrofit approach, which the BART Board then certified. And based on that we sized the bond to meet that need.”

Host:

“And that work’s been going on for years now. Tell us what’s been done to the system.”

Horton:

“Well, it’s probably easier to describe what hasn’t been done yet. Out of the overall 90 some miles of work that we had to do, we have only about four miles of aerial structure left. It’s on the Fremont line. We’re working on that now, in fact it’s mostly in construction. And then we have further retrofits on the Transbay Tube and that’s it. That’s all that’s left to do.”

Host:

“Wow. And it sounds like the money has been well spent. Can you speak to that?”

Horton:

“Well, what we can say is that first of all the original overall program budget was $1.307 billion, we had funds from other sources, it has been reduced by about 30 million dollars and we still expect to finish the work. In addition, we’ve actually been able to accomplish more work than was in the original scope because we were able to save money on the retrofits in the early stages, which we are now plowing back into the system to get more performance, if you will.”

Host:

“I think one of the areas on the system that people are always interested in is the Transbay Tube. It’s just the miracle of engineering. Talk about the earthquake safety level for the Transbay Tube. What’s been done there and how safe is it?”

Horton:

“Well, we are designing the retrofits for the Tube to a much higher level than for the rest of the system. So we’re talking about very very rare earthquakes here, ok? In the most devastating earthquake, which we define as a 1,000 year event something that might happen once every thousand years, we expect that the Tube could crack and leak. Not fail, just crack and leak. And leak enough that we would want to evacuate it and fix it. That’s the retrofit we’re getting ready to carry out. We have already done retrofits sufficient to make it safe for pretty much any earthquake below that level. I mean we have looked at for example the 500 year event and the Tube survives pretty well, it doesn’t really have any significant problems. So really we’re looking at this very very large earthquakes and as such then our riders should feel pretty comfortable that unless there’s a real sort of Armageddon-type event, the Tube should survive ok.”

Host:

“Can you say similar for the rest of the system that has undergone this retrofit work?”

Horton:

“Well, the rest of the system we designed for a 500 year event for safety, which means that the system won’t fall down and will protect people from major injuries but you wouldn’t want to run trains on it afterward. For a smaller event, we have also designed it to remain operable. Again, a 500 year event is pretty rare. It doesn’t happen that often, so our riders, the probability of being caught in that is very very low.”

Host:

“I’m speaking with Tom Horton, he’s the group manager involved with the Earthquake Safety Program. Of course many long-time residents in the Bay Area will always think back to 1989. The Loma Prieta Earthquake. Everybody knows where they were when that happened. Really an incredible story for BART. As you know, it was just a matter of hours before service was restored on the system.”

Horton:

“Yes that’s correct. And it actually taught us a few things about how to go about evaluating our structures because as you know the earthquake epicenter was down near Watsonville, way way south so you would expect the damage to be say in Fremont, which is the closest area to the earthquake. In fact the only damage we sustained was at the, right at the Transbay Tube on the east side. And they were able to repair that within a few hours and put the system back into operation. And of course it served a very vital purpose for the first 30 days or so while the Bay Bridge was being repaired.”

Host:

“I know one of the areas still that’s being looked at, the Berkeley Hills Tunnel. Talk about the status right there and what are some of the options there going forward?”

Horton:

“Ah yes, the Berkeley Hills Tunnel. The main issue there of course is that it crosses the Hayward Fault in the tunnel so if you get an earthquake large enough the earthquake, the fault will actually displace, which is another name for saying it’ll move. And you will get a break, the tunnel will break and when tunnels break they don’t just sort of break you’re going to see concrete falling and things like that. That’s a very very difficult problem to solve. Especially when you’re talking about the kinds of movement that we’re talking about. You could see four to five foot offsets there, very large and tunnel liners just aren’t built to take that kind of movement. So at the time of the original program, we couldn’t really identify a practical fix for this. There just wasn’t something out there that we could think of. More recently, we’ve been looking at some new methods that involve creating what we call a segmented liner. Instead of being continuous concrete through the fault zone, it would be a series of rings, concrete rings, large enough so that if the tunnel offsets there will still be enough room for the train to get through. So these are oversized rings, right? So if they move by four feet, you will still have enough room for the train to get through. And because they’re rings they can slide against each other, move across the fault and minimize the loss of tunnel, and be able to put it back in service fairly quickly with a certain amount of repair.”

Host:

“So where are we at in terms of like trying to move forward with that? I mean obviously that sounds like a long term approach.”

Horton:

“Yes, it’s very expensive. We’ve presented the alternatives to the BART Board. They are aware of it. The problem now is finding funding to do it. And we’re talking very large sums of money so it’s not easy to do.”

Host:

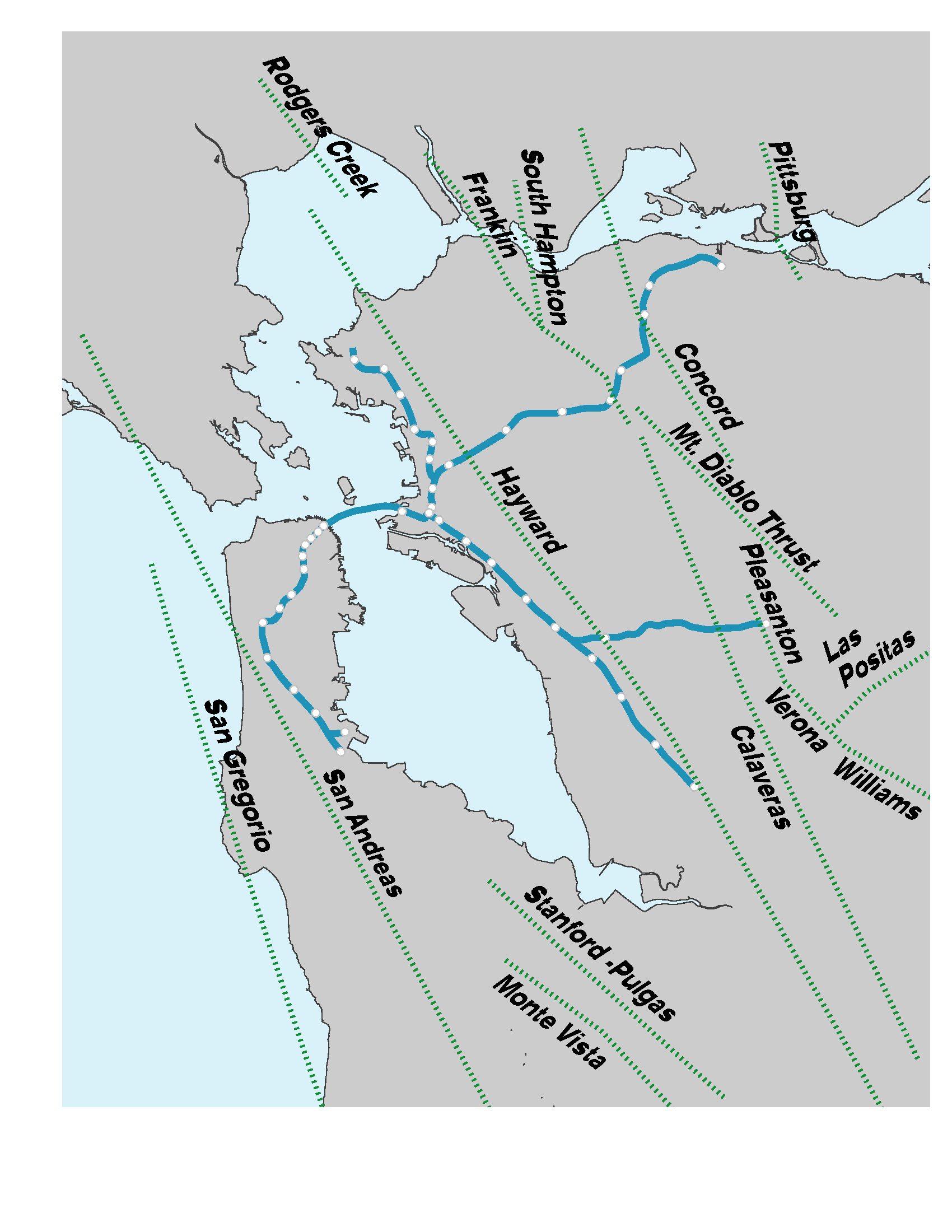

“And the fact of the matter is, in the Bay Area we are just going to be surrounded by earthquake faults. We have the San Andreas Fault along the Peninsula in San Francisco, we have the Hayward Fault in the East Bay among many others. We just got a reminder recently there was 3.5 earthquake in Piedmont. I mean this is one of the things we just have to live with.”

Horton:

“We do. The unique thing about the BART Tunnel is that it is crossing in tunnel. Most of the other faults you’ve mentioned either were not crossing the fault or were crossing it what we call at-grade which means along the surface or in an aerial structure. Those are much easier to retrofit for a fault offset than a tunnel is. And that’s one of the reasons the Berkeley Tunnel is so difficult.”

Host:

“Talk about the new technology involved. I think it’s fascinating that there’s an earthquake warning system out there and BART is participating in that. Kind of talk about how that works and whether it’s come into play yet.”

Horton:

“The earthquake warning system isn’t strictly part of the earthquake safety program so I’m not as familiar with all of the details. But it’s a system that utilizes the existing network of seismometers and other instruments all over the Bay Area to identify the earthquake and its location very quickly and pass that information to other places. Because of course the earthquake waves are going to travel, it takes a certain amount of time for them to travel from place to place and our new electronic devices if you can get the signal fast enough you can actually warn the group before the earthquake wave gets there. That’s the basic idea. Now we’re not talking about a lot of warning, we’re talking about anywhere from a few seconds to a minute worth of warning. But with that you can do things like sound alarms. There’s one I know of for example a fire department that’s going to open the doors to all their fire stations so that if the earthquake hits and the doors rack, they won’t have them stuck shut they’ll be open. So things like that you can do. In our case we could slow the trains down so that when the earthquake hits there’s not as much throwing around of the passengers if you will. And things like that can be done.”

Host:

“Coming back to the work that’s been done under Measure AA. The changes that have made, the retrofits, is it anything the passengers will notice or is it just kind of so built into the system it just kind of mixes into the environment of the stations?”

Horton:

“We like to say our work is work you’ll never see. Most of it is underground and has been buried so you can’t see it. That’s the footing work. There is some work on what we call the peer caps, which are the big hammer-headed things on the top of the column that you see out there. Some of those you’ll see have been thickened and maybe they’ve been expanded a little bit. If you look sharp you can see them, but basically that’s difficult to see. None of this effects the passengers directly, they can walk right by it and it doesn’t bother them. But if you wanted to look for it you could see some effects of what we’ve done.”

Host:

“Looking at all the work that BART has put in, I mean this is a process that has gone on for more than a decade. How confident are you in the system? I mean you told me some of these structures are ready for a 500 year event, that sounds like a really big thing to be prepared for.”

Horton:

“Yes and we’ve taken that seriously. I mentioned that we’ve saved money earlier throughout the time that we’ve done our engineering and such we’ll save money but not if it compromises the performance of the system. That is paramount. And we do have pretty good confidence based upon, we’ve run scenarios for example earthquake scenarios, that show that these structures are going to pretty much behave the way we expect them to behave in these large earthquake. Now a lot of it of course depends on where the earthquake hits, right, if it’s right near the system versus far away. We have tried to use the worst possible case that we can think of to do these designs. That makes us pretty confident that wherever the earthquake hits we should be ready for it.”

Host:

“And just to wrap it up for riders that are on their commute, I mean 430,000 people a day and growing. How safe should they feel as they ride on the BART system?”

Horton:

“Well, let’s put it this way. They’re probably safer in the BART system than they would be in many of the buildings around the Bay Area which have not been retrofitted for these types of earthquakes. And so if you want to feel safe get on the BART system versus being in certain buildings. Now of course the modern office buildings are better. But many of the older builds in the East Bay aren’t ready for these earthquakes and will probably cause more damage than will to the BART system.”

Hoston:

“Thomas Horton with BART’s Earthquake Safety Program thanks so much for joining us and thank you for listening to the latest edition of “Hidden Tracks: Stories from BART.”